Starter Kit for New (Positional) Callers

I offer this material in the spirit of community. If you use it, please let me know! And please credit

me when and where possible.

For other workshop videos and notes, do also look at the Caller How-tos!

- How to Call: New Caller Starter Kit (positional focus)

- Building Your Dance Library and Repertoire

- Sharing Your Positive Attitude

- Callers as Leaders

New Caller Starter Kit

Although this is aimed at new contra callers, a lot of the advice applies equally well to calling ceilidh, Playford/English, or any other sort of called dance.

Statement of Purpose

The intention of this "starter kit" is to offer new callers information that supplements the work we do together in the Scissortail caller workshops. It assumes that you've been dancing long enough to understand basic contemporary contra dance terminology from a dancer's perspective, if not yet from that of a caller or musician. Our caller workshops meet monthly, taking up a different topic each time, as well as offering the opportunity for calling practice. Everyone workshops at their level; although I nominally organize the workshops, experienced callers attend and offer their experience and expertise, and callers at all levels have the opportunity to practice calling dances that challenge them. New callers also contribute experience and expertise, as do dancers who attend in support of the callers. This document is not comprehensive, but it's a starting point!

A note about language: I call positionally and role-free, by which I mean, I teach walkthroughs and call dances without explicit reference to the different roles within a partnership. The examples I give in this "starter kit" use positional language. It is important to note, when calling positionally, that a contra dance swing still requires a binary pair made up of people consistently dancing the same "side" of the swing. Most contra dancers negotiate this with their partner as they line up, but new dancers will have to be taught this, either by an experienced partner, the caller, or in the course of an introductory workshop.

Table of Contents

- Dance and music structure

- Planning how you'll teach the dance

- Planning your calls

- Four easy contra dances with diverse figures

- Links to recordings for practice

- What to expect at a caller workshop

- Why I use positional calling

- Other great resources for new callers

1. Dance and Music Structure

Most contra dances consist of choreography set to 32 bars/measures of music, broken down roughly

into four sections with 16 beats of music (which is equivalent to eight measures) in each section.

The accompanying music is described as square, and consists of two-part tunes, each of which part is

repeated so that there are four parts, matching the four parts of the dance (or vice versa, depending

on how you look at it!). Callers write out this structure on their dance cards as follows:

| Dance Title | |

| A1 [dance figures] | The As are the first half of the tune, and the Bs are the second half. |

| A2 [dance figures] | |

| B1 [dance figures] | All four sections together are one time through the dance. |

| B2 [dance figures] |

As a new caller, what you need to know is how long each figure takes—how many counts of the 16 in each section—and when to prompt the dancers to do them.

But before you call the dance, you have to teach the dance. We call the teaching portion of

calling the walkthrough.

2. Teaching the Walkthrough

To teach a walkthrough effectively, you need to know the dance very well. It also helps to take a moment to reflect on what helps you learn and remember a dance.

Write down three things that you've found particularly useful in walkthroughs. If you aren't sure, wait until you're at a dance or a workshop, and pay attention to the walkthroughs, and to which parts of the walkthrough you use most as you dance.

Here are the steps I take when I'm developing a new walkthrough:

- Walk through the dance myself, from every position in a hands-four. Does it work? Does it progress?

- Think about transitions between figures: are there useful moments of flow or connection that will help dancers remember the sequence?

- Identify "recovery" moments and locations. When are you with, or opposite, your partner? Your neighbor? Are the ones above or below the twos? Once you've identified these moments, make notes about what information you should ensure dancers know before they begin. For example, it might be useful to identify the ones and twos, if knowing whether you're above or below is important. Or, in a Becket formation dance, it might be useful to ask dancers to identify their "home" side of the set.

- Is there anything unusual in the dance? Work out a concise way to describe it.

- Teach yourself the dance, talking out loud. Note moments where you could be more clear or concise, or where you could add a location tip to help keep dancers oriented. Repeat this step until you have a solid walkthrough that you're comfortable speaking aloud.

There are some generally agreed-upon rules for walkthroughs that are also useful to keep in mind:

- Use as few words as you need to teach effectively.

- For unusual figures, have two different ways to describe it. Or, which is sometimes the better choice: do a demonstration! If you decide to do a demo, make sure you're prepared for it ahead of time.

- Use the present tense. "Neighbors, allemande left halfway" is a more effective instruction than "Neighbors are going to allemande left halfway," for several reasons.

- Unless you have a good reason not to, stick to the "caller order of operations": who, what, how far — as in the example above: "Neighbors, allemande left halfway" — and into which next figure, eg, "into a left-hand star all the way."

Finally, you might be wondering how you walk through a dance for four people — or more! — when

there's just one of you. Many callers use props, like coins, chess pieces, salt and pepper shakers,

etc., to "walk through" dances. It's a great way to verify that the dance works, and to visualize

who is where, when.

3. Planning Your Calls

Calling the dance is a separate skill from teaching the walkthrough. Ideally, the walkthrough began the process of memorization for the dancers; calls therefore function as reminders, rather than full descriptions. For most of your calls, you'll have four beats of music to convey the critical information (who, what, how far) to dancers. If your walkthrough was strong, your calls can be more concise.

Recommendations for planning your calls:

- Be consistent. You don't have to be robotically exact with your wording, but dancers will get used to hearing certain phrases, and respond more easily to them. If you always say "chain across," the dancers will soon respond as soon as they hear you say "chai—"

- Be willing to experiment if your call seems less effective than you expected. Does it need to be earlier, or in a different order?

- Be aware of figures or sequences with unusual or fuzzy timing, and plan your calls accordingly.

- Not sure how to phrase something? There are tons of contra dance videos online: you might even find one of the dance you're working on. Regardless, videos can help you figure out what to do — and, sometimes, what not to do as well.

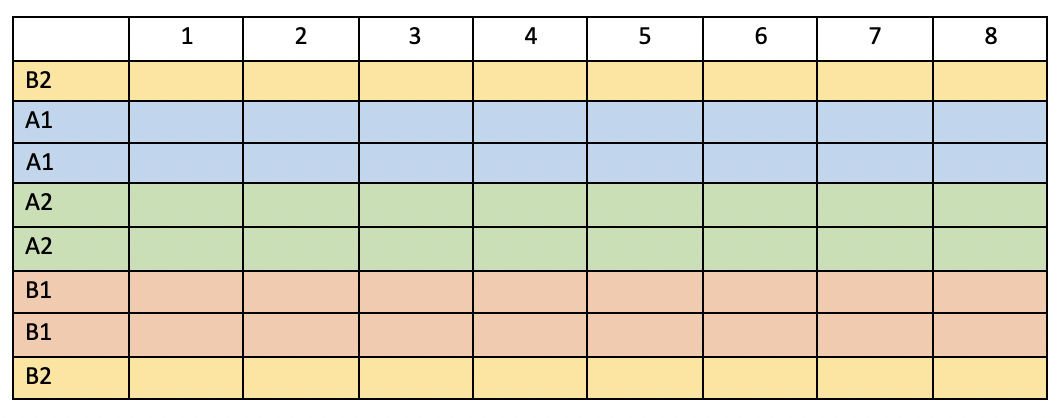

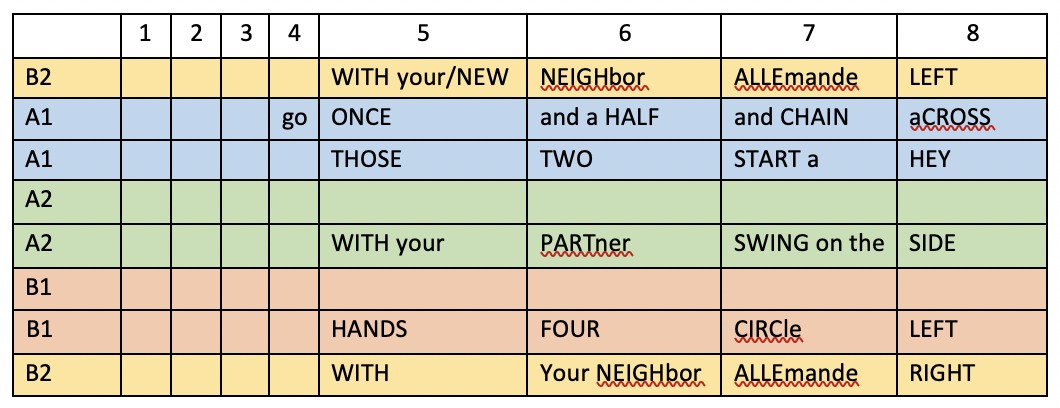

The most fundamental rule of calling is to call the figure before it is supposed to happen. This can feel counterintuitive to new callers, who are used to responding to the music as dancers, and are therefore tempted to call the figure as it begins. Callers have long used a chart to help train themselves out of that tendency; it looks like this:

Note that the B2 is split; why is that?

You can copy this table and use it to write out calls. Let's try filling it out for the dance, Delphiniums and Daisies, by Tanya Rotenberg.

Here's the dance:

Delphiniums and Daisies

Tanya Rotenberg, 1985

Improper

A1 Neighbors allemande left 1 ½; Chain across by the right

A2 Pass right shoulder for a full hey for four

B1 Partners long swing

B2 Circle left three places; Neighbor allemande right 1 ½

And here's how I'd fill out the chart, with all caps marking where I hit the beat:

What information did I leave out, compared to the dance instructions? What information did I add in, and why? How might you call it differently?

4. Four Relatively Easy (But Not Boring!) Contra Dances

Greetings

Tori Barone

Improper

A1 Neighbor balance and swing (stay connected to your neighbor; one of you has a right hand free)

A2 Long lines, forward and back; just two, allemande right in the middle once and a half

B1 Partner balance and swing

B2 Long lines, forward and back; circle left three places and pass through

Salmon Chanted Evening

Steve Zakon-Anderson

Improper

A1 Neighbor allemande right 1 ½; two in the middle, allemande left 1 ½

A2 Partner meltdown swing

B1 Chain by the right across and back

B2 Right and left through across; circle left three places and pass through

Simplicity Swing

Becky Hill

Improper

A1 Neighbor balance and swing

A2 Circle left three places; partner swing

B1 Long lines forward and back; chain across by the right

B2 Left hand star all the way to a new neighbor; new neighbor, do-si-do

You Can Get There From Here

Linda Leslie

Dance starts in short wavy lines: from improper formation, neighbors take right hands; ones are facing down, twos are facing up.

A1 Waves balance and Rory O'More slide to the right; waves balance and Rory O'More slide to the left

A2 Neighbor balance and swing

B1 Circle left three places; partner swing

B2 Circle left three places (and re-form your wave); balance this wave and walk forward (to make a wave with new neighbors)

5. Links to Recordings With Which You Can Practice

Youtube has a ton of contra dance music: the Portland Selection collections are some of the best to practice to.

What should you look for when you're seeking out practice music?

- "Four potatoes": the four beats of music before the tune starts give you an opportunity to make your first call, and also are a useful benchmark for new callers to nail the beginning of the tune. Not all recordings are intended to be danced to, so they won't all have four potatoes, even if they're contra dance tunes.

- Clear phrasing: particularly useful for new callers are recordings that have clear phrasing and rhythm. Some contemporary bands like to experiment with tunes on recordings, going into drone- or trance-like riffs on the melody, or even dropping it altogether. It's beautiful, but it can be very hard to call to!

- Different styles of tune: can you tell the difference between a jig and a reel? Can you describe the quality of tunes using adjectives like bouncy, smooth, driving, cheerful, bluesy? How do you, personally, tell different tunes apart?

6. What to Expect at a Caller Workshop

As I mentioned at the beginning of this document, our caller workshops take up different topics depending on who plans to attend and what we all want to work on. They're not quite a formal sequence, but they also don't repeat the same introductory material every time.

Having said that, a lot of our workshops do include some opportunity for callers to practice calling, and this ranges from new callers making their first attempt, to experienced callers working on tricky material. It's always useful to practice calling a dance you've never called before! And the primary advantage of our workshops is that everyone present is there to support the learning process.

Central to that process is giving feedback, and we do it in a very specific way:

- If they want to, the caller identifies specific aspects of the teaching/calling they're trying to work on before they begin.

- The caller teaches and calls the dance.

- The workshop coordinator asks the caller to reflect aloud on how it went.

- The coordinator asks the caller if they want feedback from the room.

- If the caller says yes, people are invited to offer their experience, using "I statements" rather than "You should have…" to do so. For example, a dancer might say, "I didn't hear you say that the do-si-do was once and a half, and so I didn't progress." They wouldn't say, "You should have told us the do-si-do was once and a half!"

- The caller is encouraged to take notes, but not to respond to individual feedback straight away — although we often make exceptions to this if the caller agrees with the feedback and wants to solicit suggestions or get feedback about a solution they've already come up with.

- The dancers (including other callers) are not allowed to give unsolicited advice.

- If the caller declines feedback in the moment, they are welcome to solicit it later from the workshop coordinator or others who were present at the workshop.

Other topics we address at caller workshops are: programming a dance evening; working with musicians;

writing better dance cards; creating a sense of community; collecting dances and building a repertoire;

parsing dance difficulty; working with beginners (how to teach an intro workshop); gender-free calling;

using demos; and more!

7. Why I Use Positional Calling

Most simply, positional calling reflects the reality of modern urban contra dance, in which people often expect:

- To dance with partners they enjoy, regardless of gender

- To dance with a romantic partner, regardless of gender

- To be able to dance both sides of the swing

- To intentionally switch sides with their partner throughout a dance

Of course, not all dancers want all these things, but several of them are made difficult, uncomfortable, or even impossible when dance roles are gendered. In other words, although historically each side of the swing was sometimes gendered, that is often no longer the case. Using gendered language confuses new dancers because it implies they can expect the actual dancers they encounter to be gendered in the same way — and when that isn't the case, gendered language doesn't do anything useful for experienced dancers, either.

Various strategies for gender-free dancing have existed for over thirty years, and range from positional calling

to alternative role names — some of which required physical markers, like 'bands and barearms,' and some of which

rely on dancers to self-identify, such as the currently-popular 'larks and robins.' I have called with several of

these systems since beginning to explore gender-free possibiltiies, and in my experience, positional calling has the

most positive results for dancers: they don't need to remember a new role term, which is often unfamiliar and brings

an extra mental load, and positional walkthroughs emphasize transitions and flow (or punctuation!) in a way that

traditional role-based walkthroughs often don't—making the dance easier to remember.

8. Other Resources for New Callers

You can find other workshop topics, including videos of my positional calling workshops, on my Caller How-tos page.

The Country Dance and Song Society (CDSS) has a Resource Portal that includes a ton of links for callers at every level of experience.

In fact, it's so comprehensive, I'm going to stop there!

...Well, maybe one more link, to the CDSS Store, where you can buy music, dance collections, and more. You can also buy music directly from musicians at dances, or from online sources like Bandcamp.

Becoming a member of CDSS - or, in the UK, the English Folk Dance and Song Society -

supports all of us, and brings you into a community that sustains traditional dance, music, and song.

Building Your Dance Library and Repertoire

This set of notes is based on a caller workshop I organized for Scissortail Traditional Dance (Oklahoma) on March 29, 2020. The theme was building repertoire: how do we do it, and what are the challenges?

One of the best ways to build your dance library is to collect while you're at a dance. For the most part, callers will be happy to share a dance or two (or three!) with you at the end of the evening—but please wait until the end so that you aren't interrupting their preparation and work. Try to remember the name of the dance (you can ask straight away for the title, if the caller didn't say it), or some of the signature figures if not. Don't ask callers for their entire program; if they're open to that, they will offer it.

Collecting at dances isn't always a foolproof strategy. For one thing, if you're at a local dance, you don't want to collect a dance one week and call it to the same community a few weeks later. For another, if you collect dances at special events like dance weekends, or camps, you might get an imperfect impression of how difficult (or easy!) the dance is—and then struggle to teach it to a room full of inexperienced dancers. Finally, keep in mind that dance tastes change over time; the dance that everyone loved five or ten years ago might not be the most popular dance today.

This particular workshop was held while we were under a shelter-in-place recommendation, and all of our dances had been suspended indefinitely—posing another impediment to the practice of collecting dances directly! So I gave our callers a prompt that, I hoped, would engage our spirit of collaboration: bring three dances to the table that you find yourself turning to regularly to solve a particular problem, and be prepared to explain how each dance does so. Unsurprisingly, everyone came over-prepared—so we generated an impressive list of dances. Dance instructions for everything in this Appendix are available in The Caller's Box, a database produced by Chris Page and Michael Dyck (note that in some cases, the Caller's Box will link you to the instructions on another site).

Before we started sharing our dances, we had some general conversation about choosing dances:

How do you determine the difficulty level of a dance?

Two things make a dance hard: the choreography, and the quality of the walkthrough. As a caller, you have control over both.

To assess the choreography: in an ideal world, you would workshop a new dance to work out its quirks. But often, that's simply not possible—so look for these things:

- Is there obviously unfamiliar or complicated choreography?

- Does the dance have a high piece count*?

- Does the dance have an intuitive flow?

- Will the choreography require a demonstration?

- When in doubt, do a demo!

- How many new things, at any level of difficulty, will you need to teach?

- Are there deceptively simple-seeming figures that always challenge dancers, such as a circle all the way?

- How precise is the timing required by the dance?

- Are there any recovery points in the dance (long lines, balance and swing)?

- Does the dance have a clear or memorable storyline**?

Assessing the choreography is also context-dependent:

- How much have you already taught?

- What is the experience level of the dancers?

- How tired are your dancers?

You already know the principles behind a good walkthrough. How will you apply them to this dance? Will your walkthrough be relatively quick, or do you anticipate needing partial or multiple walkthroughs?

*Piece count: the number of individual figures in a dance. In rare cases, two figures are so frequently done together that they count as one: a balance and swing, for example.

**Storyline: a dance's storyline describes the logic of its choreography, for example in terms of flow, or a succession of interactions, or a pattern that builds on itself.

Note: You may find that after you've called a dance, you want to reassess your evaluation of its difficulty. Make notes straight away about how the walkthrough and dance went. Where did people struggle? What surprises were there? I make notes directly on my card so that I can't misplace them, or forget to incorporate them into my next walkthrough.

What kind of music should you ask for?

This is a question that you'll hear asked in different ways—and that you will have to answer differently for different musicians. Traditionally, a caller might be asked if they want "jigs or reels," or, if they're an old-time band, they might not ask anything at all! As you call more often, you'll discover that there's quite a lot of variety; some musicians will simply ask to look at your dance card and make the decision themselves, and others will want precise input.

Here are some things to keep in mind:

- Talk to the band! Ask them what they want from you, related to tune selection. Almost every dance band will want to know where the balances are, at the very least.

- Develop your own system of describing what you want: the core information should be about character and tempo. Do you want a cheerful, fast tune, or a smooth tune taken at a relaxed pace? Is there an energy arc that you want to play out over the whole evening?

- Bands will also have opinions about the flow of the evening, and which sets they want to play when. Work with them! Alternatively, they may want the caller to take a firm and clear lead. Work with that, too!

- It can be useful to make a note of the tune(s) the band chose when the music seemed to match the dance really well, but also write down a description of how it felt—not all bands will play a tune the same way.

- It's okay if you aren't a musician yourself, although you might want to learn some basic vocabulary as you develop your calling skills.

What kinds of dances do we always seem to need?

- Great first or second dances of the evening

- Dances that introduce basic figures like a chain, or a hey

- Dances with great flow, good storyline, and interesting progressions

We noted that all of these questions would be good candidates for submission to the contra callers email list, hosted by Shared Weight and sponsored by CDSS.

So... What are the dances we keep coming back to?

Sandy Knudson chose some dances with unusual figures, in order to diversify a program.

- Trip to Peterborough (Rick Mohr): long wavy lines up and down the middle of the set

- A Good Feeling (Bill Pope): orbit

- The Cows Are Watching (Bill Pope and Judy Goldsmith): zig-zag

- Boys From Urbana (John Coffman): zig-zag

Carol Barry chimed in with some other zig-zag suggestions:

- Rocking Robin (Rick Mohr)

- Weave the Line (Kathy Anderson)

And someone else suggested another dance with waves up and down the middle:

- Long May It Wave (Melanie Axel-Lute)

Sandy also brought us some dances that introduce a particular figure in an accessible way. The potential benefit of dances like this? They also mix up a program, and they can be a useful gauge for whether that trickier dance with the same figure will be a success later in the evening.

- Microchasmic Triplet (Ann Fallon): triplet with contra corners

- Beck and Call (David Smukler): short-wave Rory O'More

- Earl & Squirrel (Chris Weiler): short-wave Rory O'More

Louise added:

- You Can Get There From Here (Linda Leslie): short-wave Rory O'More

Noel Osborn chose dances with great transitions: which might mean unusual, but always means fun, with great flow.

- Al's Safeway Produce (Robert Cromartie)

- Star Trek (Mike Richardson)

- Streetsboro Reel (Becky Hill)

Carol added some more dances to the conversation:

- David's Guiding Star (Steve Zakon-Anderson): has a star transition like Star Trek

- You're Among Friends (Bob Isaacs): borrows from Al's Safeway Produce

Carol chose "infrequent favorites": dances that she loves, but that are so distinctive she doesn't call them very often. These dances can be, but aren't always, more challenging.

- Tropical Gentleman (Kathy Anderson): "Celtic hey" figure – worth it!

- Whirligiggin' Around (Cis Hinkle): a unique repeating gate figure; run it short!

Eric Garrison also brought in dances that are challenging and distinctive. He particularly looks for dances that offer experienced dancers an opportunity to embellish the basic choreography.

- Kinematic Dolphin Vorticity (Luke Donforth): benefits from a demo; dolphin hey

- Ramsay Chase (Joseph Pimentel): unexpected choreography, delayed gratification, and easy to switch roles. On the other hand, it's very clockwise, so benefits from being run short.

Noel contributed:

- Honor Among Thieves (Penn Fix): chase figure has a similar energy to Ramsay Chase.

And Carol offered:

- Joyride (Erik Weberg): also has a similar feel without being so complicated, and has amazing flow.

Rebekah Valencia came to the original prompt from the perspective of helping new callers build their dance library, so she focused on accessible dances that she relies on, and about which she has received compliments and other positive feedback from dancers.

- Citronella Morning (Bill Olson): 3 petronellas in a row; great right after a hard dance.

- Here and There (Chris Page): Down the hall and stay there; good beginning or ending dance when you have a lot of space in the hall.

- Coffee Grinder (Jim Hemphill): Becket, ends with a partner swing, has a roll away.

Louise concluded our discussion of individual dances with a pair of dances that she puts at the very end of the evening—a moment where, depending on the band and the dancers, you want either a high-energy, blowout dance, or a smooth, romantic flow.

- Old Time Elixir #2 (Linda Leslie): the former, with petronellas that take the evening out with a bang. Linda notes that this is the same choreography as Tica Tica Timing (Dean Snipes)—a coincidence.

- Butter (Gene Hubert): a classic ending dance with gorgeous, no-thinking-necessary, smooth flow.

Sharing Your Positive Attitude

As we transitioned to Zoom dances this spring (2020), I made a brief instructional video for our dancers. Chatting about that video — and my parallel shift, as a university professor, to online classroom teaching — with a friend of mine, I wrote, "It's a challenge to teach in an entirely new format. We've all spent decades honing in-person teaching techniques, and now almost none of those skills apply. [I had to] shift from 'why isn't this working?!' to 'oh, here's an opportunity!' -- and the video came about because I was trying to think about the opportunities for dancers, rather than the frustrations, in this situation."

We all get flustered when things don't go right. One of the biggest challenges for me as a new caller (and teacher) was learning to meet every eventuality with equanimity. Sarah Van Norstrand is a master of this skill — she consistently radiates calm joy, no matter what happens on the floor.

All this is a long way of saying, this workshop is about caller attitude. So I asked my fellow callers:

- What have you noticed callers doing that made you feel valued and happy, as a dancer?

- How, as a caller, have you learned to reframe frustrations as opportunities, both for yourself and for the dancers?

- What strategies are there for learning to enjoy situations that initially made you uncomfortable?

- What do you do, as a caller, to mitigate the dancers' discomfort when it appears - and how/when do you notice that discomfort?

Colin Hume has suggested that attitude is more important than skill - or, we might say, attitude is part of the slate of skills that a caller needs to be successful. He points out that a question fundamentally related to attitude is "why do you want to be a caller?" — so we talked about that, too.

This workshop took the form of a conversation, which I've reproduced below.

Some key lessons emerged:

Rebekah: During the Pat Shaw Centennial year, we were doing a Pat Shaw dance at every regular English session. Many of his dances are quite challenging, and for various reasons, we often saved them for the end of the evening. Just before one such dance, I remember Carol saying, "It's going to be a mess, and we're going to have fun." And it was a mess, and we all had fun.

Carol: Early on, I'd sometimes miss the hard parts when prepping a dance. I'd figured out that if a dance got rocky, the best thing to do was to say "find your partner and swing!" and then move on. Once, after that happened, John Hinkle came up to me and said, "Boy, that was the most fun I've had on a dance floor." And I don't know if it was true, but it was exactly what I needed to hear.

A big part of it is reminding yourself that you're there to have fun, and everyone else is there to have fun - don't take it so seriously!

Sandy: I'm a communal person; the reward for me is seeing people have that "ah ha!" moment or a moment of joy. It doesn't feel like work to me.

Louise: It has felt like work to me when I feel responsible for things I can't control; I had to learn to let go of the bubble of chaos that you can't fix. It's important for me to be prepared; if I know I've done my homework, and feel confident about the aspects of a dance that I should be in control of, I have fun.

Rebekah: Your program is part of your attitude. If it's at an appropriate level for the dancers, you'll have the space to be relaxed, confident, energizing, and inspiring. Also, you can fake it 'til you make it: your confidence will be infectious. Confidence is partly calmness - just do what you do, and allow people to adjust/come to you.

Eric: What do you do about the bubble of chaos when it's already evident in a walkthrough? This often happens when new dancers show up a bit late and partner with each other in a clump at the bottom of a set.

Rebekah: You can use the walkthrough to progress them away from each other. If they're struggling with timing, do a demonstration or talkthrough while doodling to give them a sense of how quickly they need to move.

Louise: If a lot of new dancers arrive late and are sticking together, consider calling a mixer instead of the duple minor you had planned - integrate them into the group as quickly as possible.

Sandy: And reassure them: "It's okay, you'll get another chance to try that." Or simply give them permission to skip a figure and move on: "There are no contra police." Often, you want to steer into the skid: if you stop, you're going to lose them, so keep people moving.

Carol: International Folk Dance was an interesting way to start calling, because you didn't think of yourself as a "teacher." Everyone shared the teaching responsibility and there was no expectation of expertise - it was very communal.

I sometimes think about Bruce Hamilton's observation about good English dancing - that the dancer should arrive "almost late" for the next figure - and am reminded that perfection is actually not perfect. English dancing is teaching people to find the connection between the dance and the music.

Sandy: Will Mentor once said at a workshop, "I'll share my whole program, all my notes - I can give you my lesson plan, but you still need to do the work." It's instructive to see callers doing that work: Bob Isaacs holds instructional workshops where you see the intentionality of his choices. Is a dance neighbor-oriented or partner-oriented, for example? He has a very analytical approach to programming and calling.

Carol: Kalia Kliban is very willing to come down and do a demo, precisely and quickly. And her programs are excellent.

In contrast, when a caller comes down and says, "here's what I'm seeing," and then emulates dancers making mistakes or lacking in style, instead of saying, "here's what we're going for" and demonstrating good dancing, or the correct figure, it feels uncomfortable. How can we frame correction positively?

Pointing or singling out people who are struggling is also unkind, and contributes to a negative atmosphere.

Louise: When a caller says (or implies) that "You [dancers] are here to look good for me," it sets them up as judgmental rather than instructive or encouraging. On the other hand, complimenting the dancers when they do have great energy always feels good.

Context determines how much instruction or correction is appropriate; callers can do everyone a favor by clarifying the intent of the event. Is it a class, a workshop, or a regular dance? Are people expecting critique, and seeking correction? Even if the dance is advertised in a way that implies more instruction than usual, it can be helpful for the caller to reinforce that expectation. Carol often says, "this is a class, so let's take a moment to work on this," at our regular English dances.

Rebekah: Andrew Shaw once went around the whole floor at an advanced workshop asking each set to respond verbally about whether or not they had it; he was asking us to take responsibility for our own learning, in parallel with his teaching. Will Mentor chooses beginners to help him with demos; it boosts their confidence, and is an inclusive choice.

Sandy: I say to our new dancers, "Dancers are great problem solvers." And I make sure I share my agenda with them: for example, I tell them: "I want to teach you contra corners, so we're going to do this set dance that introduces the figure, and then, if you stick around, in the second half we'll do another dance with contra corners and you'll be blown away by your skills."

Louise: Chatting with dancers before things get going or at the break can help them feel welcome, and offers an opportunity to share the agenda. In intro workshops, or at the beginning of the dance, for example, I try to give people an overview of the general shape of the evening.

Carol: Scott Higgs calls out the tricky parts of dances by saying, "Here's the fun bit" - it ensures that people pay attention, but isn't intimidating. Joanna Reiner points out "key moments" in dances, to similar effect.

Louise: Joanna also often asks dancers to "pause" just before those key moments, which increasingly results in people making their hands into little paws. If the caller embraces that sort of silliness, it can relax people and help them learn those "fun" bits of the dance more easily.

Rebekah: Joanna also has a wonderful way of being forgiving: after teaching a hard dance, she sometimes says, "You might find a different way to do this dance, and if you prefer it, tell me about it at the end!"

Why Are You A Caller?

Louise: I enjoy the teaching aspect of calling, helping people work together to make something beautiful or joyous. It's interesting to think about why I started versus why I kept on; I started calling English because Ray Bantle, in Ann Arbor, suggested I'd be good at it, and so I thought I'd give it a shot. And then when I moved to Oklahoma, I was encouraged to start calling contra because one of the regular callers was moving away. But I keep calling because of that sense of shared creativity: musicians, caller, dancers, sound tech, volunteers all coming together to make something incredible happen, whether it's six people or six hundred. I also enjoy building friendships with people I wouldn't necessarily meet otherwise - the dance community is full of great people.

Carol: You might not have known this, but I was a second-grade teacher before I became a librarian, and I was much happier working with library patrons who wanted my help, and to learn from me. Teaching dance is similar: I love teaching people who want to be taught - to meet a need.

Rebekah: Filling a need was the start, for me, but fulfillment as a caller came from the problem-solving - putting together a strong program is like putting together a puzzle. And my own teaching experience, training people to train dogs, was helpful.

Sandy: Adults aren't that different from dogs or children! Even when I was a very new caller, I found that the skills

I had developed over a career of teaching children music transferred very easily to calling, and so it felt natural. I enjoy

calling because you have to break things down into little bits and help people put them together.

Callers as Leaders

How do callers act as leaders at a dance, and in the dance community?

- When at the mic, callers are perceived as leaders: how can we take advantage of that authority, and what should our goals be?

- When we're dancing in our own community, people recognize us as authorities even when we aren't calling. What are our responsibilities as leaders when we are dancing?

- Sometimes callers are also organizers: what sorts of things do organizers do, as community leaders?

- I've used the word community a lot; what does it mean to us? How do we, as callers, help build a sense of community?

- What challenges do leaders in the dance community face? How can we address them?

At our May 26, 2020 workshop, we discussed some of the questions above, although not all of them. I began by introducing the concept of servant leadership as a model for callers and organizers: although we are leaders in our communities, our primary goal is to empower others. In the process, we often find ourselves in difficult conversations—and here I borrow shamelessly from Bruce Hamilton, who introduced me to Non-Violent Communication as an adult (although I immediately recognized the principles from peer counseling and other early training). We didn't get through all the questions above, so we're going to have a second workshop—but I've documented the first half here for now.

What are our goals, as callers, when we are at the microphone?

Sandy Knudson: Make it fun for the band, the caller, and the dancers. I think it's important to make sure the band is having a good time – acknowledge them, thank them, be aware if they're experiencing something unpleasant even if you can't do anything about it. Know something about what they're playing: announce if they wrote the tune, or if they matched the dance really well. Be specific in your praise. Your program is a leadership tool: teach figures well, and often, and they will become beloved. Your program should build skills.

Carol Barry: Welcoming people. For instance, mentioning new people in a way that makes it clear you're happy they're there, thanking volunteers (and use that as an opportunity to describe organization structure/volunteer opportunities, and invite new volunteers).

Eric Garrison: Keeping the pace up, and keeping the dancing going.

Louise Siddons: Teaching community norms/shaping the culture, including encouraging people to embrace building skills as one of their goals.

Rebekah Valencia: Empowering people, and creating a sense of achievement – I want people to leave thinking, "I can do this!"

The discussion of skill-building led us to brainstorm about how we could do that more effectively at our regular dances.

Carol: We used to have mini-workshops at the break that taught a specific skill.

Louise: It's also okay to do a bit of extra teaching during the dance if it's focused – especially about safety, technique, or learning to "listen" to the person you're dancing with.

Sandy: You can use a dance with no new figures to focus on technique in the walkthrough.

How do we, as callers and experienced dancers, act as role models when we're not the caller?

Louise: We can help with set management from within the set – not by interfering, but by choosing to join lines with newer dancers, partnering with newer dancers, etc.

Rebekah: We can introduce new dancers to other experienced dancers after we've danced with them.

Eric: We can model listening to the caller rather than trying to explain ourselves; I say things like, "oh, this is fun, listen!"

Sandy: As an experienced dancer, you can give your partner a heads-up about unexpected things happening in line: for example, if there's a couple coming toward you who have been switching roles each time through the dance, let your partner know that they might not get the neighbor they expect, and teach them to dance with whoever comes at them. It's okay to dance twice in a row with a beginner, if they are too nervous to dance with someone new.

Eric: People who are experienced in other dance forms but new to contra or English can be sensitive about receiving feedback. How do we do that well?

- Sandy: Always ask if people want feedback before you give it.

Louise: Use "I" language: "It would help me if you put your hand higher on my shoulder," or "It helps me avoid injury if you support your own weight when we swing."

Carol: How do we encourage experienced dancers to dance with new dancers without making them grumpy?

- Rebekah: "Bonus points for the experienced dancer who dances with the most new people"; "dance with me" buttons for experienced dancers. Remind experienced dancers that everyone is better off if you help new dancers learn.

Carol: "Look for people who were sitting out that time"

Louise: Point out that it's a skill to be able to dance well with new dancers. We might even consider a workshop for experienced dancers on how to help new dancers; give them a skill set they can share, instead of an obligation. Lisa Greenleaf gave an example – that she said she could only get away with at her home dance! – of saying, "Raise your hand if you know this figure – and now everyone else, ask one of those people to dance." But that could backfire, with selfish dancers, so how do we counteract selfishness in our experienced dancers?

Useful sayings callers can make habitual:

- Social norms: "Anyone can ask anyone to dance," "You can always say no," "Dance with who comes at you"

- On expertise and experience: (With, for example, a circle right) "This is going to be easier for new dancers than experienced ones," ""The difference between new and experienced dancers is that experienced dancers have made more mistakes"

- Thanking the band by name; thanking volunteers by name

- Foreshadowing: "the dance after this will be a little more challenging," "We'll have two more dances tonight, and then a waltz," etc.

- Mixing new dancers in: "Ask someone new to dance, " "If you're a beginner, find an experienced dancer and you'll learn more quickly," "People have been arriving – ask someone sitting out for the next dance," etc.

- Dance flow: "Better never than late," "If you miss it, skip it," "Our most valuable skill is recovery," "If you're out at the ends, swing your partner and face in for new neighbors," "Dance with who comes at you"

- Positivity about the learning process: "We're here to have fun," "It's okay to make mistakes," "See? I made that mistake to show you how it's done"

Two useful models for callers/organizers/leaders

- Servant Leadership

- The leader's role is to serve others, and empower them to serve in turn

- The leader's authority comes from their effective service

- The shared goal of all in the organization is the betterment of oneself and others

- Servant Leaders seek to develop these 10 traits: empathy, listening, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth of people, and building community.

- Servant leadership has

- three key priorities: developing people, building a trusting team, achieving results

- three key principles: serve first, persuasion, empowerment

- three key practices: listening, delegating, connecting members to mission

- Servant Leaders have a tendency to see themselves as stewards of a community, which can get in the way of their responsibility to empower others

- Non-Violent Communication

- Emphasizes deep listening

- Seeks universal shared values by focusing on empathy for oneself and others

- Advocates radical self-responsibility for what we are experiencing at any given moment. Listening deeply to ourselves allows us to share our experience more authentically with others, and to hear them more clearly in turn.

- Structures listening around four components: observations, feelings, needs/values, and requests